9 Ways to Work With Objects in JavaScript in 2020

JavaScript, like tons of other languages has plenty of tricks to accomplish both easy and difficult tasks. Let's have a look at 9 ways to work with JavaScript objects in 2020 (Note: This is a list of things where I thought would make a good short list of ways to work with objects. Some are interesting, some are well known, and some are just for informational purposes)

Anyways, if you enjoy coding in JavaScript then you probably might agree with me that working with objects is a lot funner than working with other types!

1. How to Truly Create an Empty Object

Did you know that you can create objects in JavaScript? Well, of course you did!

Did you aso know that you can create empty objects?

Here's an example:

const myEmptyObject = {}This is as good as it can get when creating plain empty objects. However, internally it's not truly empty, because what you're essentially doing is something like Object.create(Object.prototype), which will create an object for you that has access to the properties inside Object.prototype, which is at the top of the prototype chain.

This means that you'll be able to use methods like myEmptyObject.toString().

To truly create an empty object you just need to pass in null when using it:

const myTrulyEmptyObject = Object.create(null)When you create objects using the approach above, no properties will actually exist until you are adding them yourself!

99.99% of the time I wouldn't recommend this as there is no point to not work up from the base prototype.

Variations of Merging Objects

2. Merging objects variation #1 (Object.assign)

const novice = { username: 'henry123', level: 10, hp: 100 }

function transform(target) {

return Object.assign(target, {

fireBolt(player) {

player.hp -= 15

return this

},

})

}

const sorceress = transform(novice)

const lucy = { username: 'iamlucy', level: 5, hp: 100 }

sorceress.fireBolt(lucy)When you use the Object.assign method you need a target object as the object to merge additional objects and/or properties to.

The target object is the first argument to Object.assign. Any arguments after that will end up being merged into the target object from the second argument onwards.

Here's mozilla's official definitiion of the method:

The Object.assign() method copies all enumerable own properties from one or more source objects to a target object. It returns the target object.

3. Merging objects variation #2 (Spread syntax)

const novice = { username: 'henry123', level: 10, hp: 100 }

function transform(target) {

return {

...target,

fireBolt(player) {

player.hp -= 15

return this

},

}

}

const sorceress = transform(novice)

const lucy = { username: 'iamlucy', level: 5, hp: 100 }

sorceress.fireBolt(lucy)When you merge objects this way, you're using the spread operator on an object literal.

This syntax made its way into the official ECMAScript 2018 Specification, so it may still be considered a new addition to some people.

It's incredibly simple to merge multiple objects this way and many people recommend it as your code can still manage to be neat and readable, because all you have to do is type three dots. That's all.

Keep in mind that the rules of merging objects still remains the same, so you can use the weirdest ways to merge objects together like so:

Spreading IIFE Functions

Functions in JavaScript are powerful in so many ways. You can practically do anything with them! This is due to the nature of how functions are in JavaScript---that they're essentially first-class citizens, so you can throw them everywhere and wreak havoc as you please!

For example, since functions in JavaScript are still objects, this means you can still treat functions as if they were objects, which means you can throw them around and do amazing things with them.

You can even use them to merge into object literals in weird ways as well, like shown below:

import React from 'react'

import {

EditIcon,

DeleteIcon,

ResetIcon,

TrashIcon,

UndoIcon,

} from '../lib/icons'

import * as utils from '../utils

export const audioExts = ['mp3', 'mpa', 'ogg', 'wav']

const icons = {

edit: {

component: EditIcon,

onClick: () => window.alert('You clicked the edit component'),

name: 'edit',

},

delete: {

component: DeleteIcon,

name: 'delete',

},

// Audio icons

// IIFE returning an object

...(function() {

return audioExts.reduce((acc, ext) => {

acc[ext] = {

component: MdAudiotrack,

title: 'Audio Track',

}

return acc

})(),

}Since IIFEs are self-invoking, we immediately return an object which is to be merged into the icons object. The result would just be the same object but with the merges:

export const audioExts = ['mp3', 'mpa', 'ogg', 'wav']

const icons = {

edit: {

component: EditIcon,

onClick: () => window.alert('You clicked the edit component'),

name: 'edit',

},

delete: {

component: DeleteIcon,

name: 'delete',

},

// Merged with audio icons

mp3: {

component: MdAudiotrack,

title: 'Audio Track',

},

mpa: {

component: MdAudiotrack,

title: 'Audio Track',

},

ogg: {

component: MdAudiotrack,

title: 'Audio Track',

},

wav: {

component: MdAudiotrack,

title: 'Audio Track',

},

}4. Checking Existent Properties in 2020

One feature that is definitely taking the community by storm (i'm sure we all agree) is Optional Chaining. This new operator takes on the form .? and permits reading the value of a property located deep within a chain of connected objects without having to expressly validate that each reference in the chain is valid.

This means that if you had any deeply nested object structure like the one below:

const food = {

fruits: {

apple: {

dates: {

expired: '2019-08-14',

},

},

},

}You no longer have to write repetitive code like:

function getAppleExpirationDate(obj) {

if (food.fruits && food.fruits.apple && food.fruits.apple.dates) {

return food.fruits.apple.dates.expired

}

}It gets much easier with using optional chaining:

function getAppleExpirationDate(obj) {

return food?.fruits?.apple?.dates?.expired

}Using it everywhere in your code just feels so much more clean.

A function like this:

function findFatDogs(dog, result = []) {

if (dog && dog.children) {

return dog.children.reduce((acc, child) => {

if (child && child.weight > 100) {

return acc.concat(child)

} else {

return acc.concat(findFatDogs(child))

}

}, result)

}

return result

}Can easily just turn into this while maintaining its readability:

function findFatDogs(dog, result = []) {

if (dog?.children) {

return dog.children.reduce((acc, child) => {

return child?.weight > 100

? acc.concat(child)

: acc.concat(findFatFrogs(child))

}, result)

}

return result

}And this only just makes you appreciate Prettier more than ever.

(Note: At the time of this writing, not all modern browsers support this feature but you can start using TypeScript today and start optional chaining all you want as it gets compiled back down to syntax that older browsers can read.

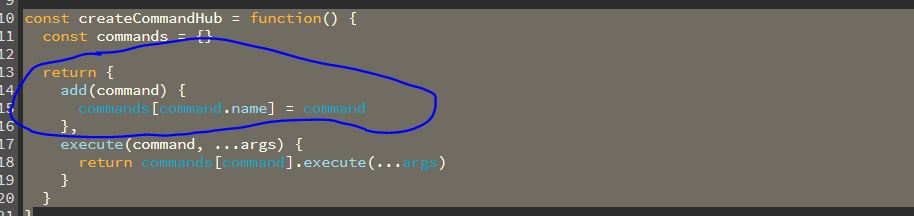

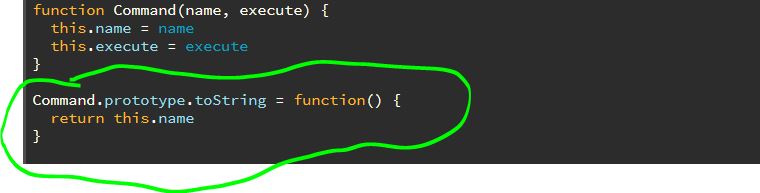

#5 Invoke Objects by Overriding .toString()

When objects are assigned as the keys of object literals, they get stringified. This brings some nice uses cases.

Let's take a look at the example below:

function Command(name, execute) {

this.name = name

this.execute = execute

}

Command.prototype.toString = function() {

return this.name

}

const createCommandHub = function() {

const commands = {}

return {

add(command) {

commands[command.name] = command

},

execute(command, ...args) {

return commands[command].execute(...args)

},

}

}

const cmds = createCommandHub()

const talkCommand = new Command('talk', function(wordsToSay) {

console.log(wordsToSay)

})

const destroyEverythingCommand = new Command('destroyEverything', function() {

throw new Error('Destroying everything')

})

cmds.add(talkCommand)

cmds.add(destroyEverythingCommand)

cmds.execute(talkCommand, 'Is talking a talent?')If you run this snippet, you will see that the code works and the result is this:

If you look closely at the way we added the command you can see that it should be throwing an error like this:

The reason why it didn't is because we defined the Command constructor we also overrided the toString prototype method as shown below:

When non-primitive type values are assigned as properties of an object, JavaScript attempts to stringify them before attaching them as the key, by falling back to its .toString method on the prototype.

@reduxjs/toolkit uses this trick to allow passing actions directly as keys, for example they can be used directly as keys map its reducer function that is assigned to the action's .type value.

6. Destructuring

Amony any great additions to the language is object destructuring:

const obj = {

foods: {

apples: ['orange', 'pineapple'],

},

}

const { foods } = obj

console.log(foods) // apples: ["orange", "pineapple"]7. Renaming destructured properties

const obj = {

foods: {

apples: ['orange', 'pineapple'],

},

}

const { foods: myFoods } = obj

console.log(myFoods) // apples: ["orange", "pineapple"]Iterating over objects

8. Iterating over an object's keys (for in)

An easy way to iterate over an object's keys is using the for in syntax:

const obj = {

foods: {

apples: ['orange', 'pineapple'],

},

water: {

f: '',

},

tolupa: function() {

return this.name

},

}

const { foods } = obj

for (let k in obj) {

console.log(k)

}

/*

result:

"foods"

"water"

"tolupa"

*/9. Iterating over an object's keys variation #2 (Object.keys)

A different approach you can use is using the Object.keys method:

const obj = {

foods: {

apples: ['orange', 'pineapple'],

},

water: {

f: '',

},

tolupa: function() {

return this.name

},

}

const { foods } = obj

const keys = Object.keys(obj)

console.log(keys)The difference here is that you'll be receiving the keys inside an array which you'll be working with. It's also more convenient if you wanted to do additional things like chaining operations and transforming into a more structured value, which is a lot more useful:

const people = {

bob: {

age: 15,

gender: 'male',

},

jessica: {

age: 24,

gender: 'female',

},

lucy: {

age: 11,

gender: 'female',

},

sally: {

age: 14,

gender: 'female',

},

}

const { males, females } = Object.keys(people).reduce(

(acc, name) => {

const person = people[name]

if (person.gender === 'male') {

acc.males.push(name)

} else {

acc.females.push(name)

}

return acc

},

{ males: [], females: [] },

)

console.log(males) // ["bob"]

console.log(females) // ["jessica", "lucy", "sally"]Conclusion

And that concludes the end of this post! I hope you found this to be valuable and look out for more in the future!