Promises in JavaScript

This post aims to shed some light on how you can use promises in JavaScripts

If you're new to JavaScript and have a hard time trying to understand how promises work, hopefully this article will assist you to understand them more clearly.

With that said, this article is aimed for those who are a little unsure in the understanding of promises.

This post will not be going over executing promises using async/await although they're the same thing functionality-wise, only that async/await is more syntactic sugar for most situations.

The "What"

Promises have actually been out for awhile even before they were native to JavaScript. For example two libraries that implemented this pattern before promises became native is Q and when.

So what are promises? Promises in JavaScript objects that represent an eventual completion or failure of an asynchronous operation. You can achieve results from performing asynchronous operations using the callback approach or with promises. But there are some minor differences between the two.

Key difference between callbacks and promises

A key difference between the two is that when using the callbacks approach we would normally just pass a callback into a function which will get called upon completion to get the result of something, whereas in promises you attach callbacks on the returned promise object.

Callbacks:

function getMoneyBack(money, callback) {

if (typeof money !== 'number') {

callback(null, new Error('money is not a number'))

} else {

callback(money)

}

}

const money = getMoneyBack(1200)

console.log(money)Promises:

function getMoneyBack(money) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

if (typeof money !== 'number') {

reject(new Error('money is not a number'))

} else {

resolve(money)

}

})

}

getMoneyBack(1200).then((money) => {

console.log(money)

})The Promise Object

It's good that we just mentioned promise objects, because they're the core that make up promises in JavaScript.

So the question is, why do we need promises in JavaScript?

Well, to better answer this question we would have to ask why using the callback approach just wasn't "enough" for the majority of javascript developers out there.

Callback Hell

One common issue for using the callback approach is that when we end up having to perform multiple asynchronous operations at a time, we can easily end up with something that is known as callback hell, which can become a nightmare as it leads to unmanageable and hard-to-read code--which is every developer's worst nightmare.

Here is an example of that:

function getFrogsWithVitalSigns(params, callback) {

let frogIds, frogsListWithVitalSignsData

api.fetchFrogs(params, (frogs, error) => {

if (error) {

console.error(error)

return

} else {

frogIds = frogs.map(({ id }) => id)

// The list of frogs did not include their health information, so lets fetch that now

api.fetchFrogsVitalSigns(

frogIds,

(frogsListWithEncryptedVitalSigns, err) => {

if (err) {

// do something with error logic

} else {

// The list of frogs health info is encrypted. Our friend texted us the secret key to use in this step. This is used to decrypt the list of frogs encrypted health information

api.decryptFrogsListVitalSigns(

frogsListWithEncryptedVitalSigns,

'pepsi',

(data, errorr) => {

if (errorrr) {

throw new Error('An error occurred in the final api call')

} else {

if (Array.isArray(data)) {

frogsListWithVitalSignsData = data

} else {

frogsListWithVitalSignsData = data.map(

({ vital_signs }) => vital_signs,

)

console.log(frogsListWithVitalSignsData)

}

}

},

)

}

},

)

}

})

}

const frogsWithVitalSigns = getFrogsWithVitalSigns({

offset: 50,

})

.then((result) => {

console.log(result)

})

.catch((error) => {

console.error(error)

})You can visually see in the code snippet that there's some awkward shape building up. Just from 3 asynchronous api calls callback hell had begun sinking opposite of the usual top-to-bottom direction.

With promises, it no longer becomes an issue as we can keep the code at the root of the first handler by chaining the .then methods:

function getFrogsWithVitalSigns(params, callback) {

let frogIds, frogsListWithVitalSignsData

api

.fetchFrogs(params)

.then((frogs) => {

frogIds = frogs.map(({ id }) => id)

// The list of frogs did not include their health information, so lets fetch that now

return api.fetchFrogsVitalSigns(frogIds)

})

.then((frogsListWithEncryptedVitalSigns) => {

// The list of frogs health info is encrypted. Our friend texted us the secret key to use in this step. This is used to decrypt the list of frogs encrypted health information

return api.decryptFrogsListVitalSigns(

frogsListWithEncryptedVitalSigns,

'pepsi',

)

})

.then((data) => {

if (Array.isArray(data)) {

frogsListWithVitalSignsData = data

} else {

frogsListWithVitalSignsData = data.map(

({ vital_signs }) => vital_signs,

)

console.log(frogsListWithVitalSignsData)

}

})

.catch((error) => {

console.error(error)

})

})

}

const frogsWithVitalSigns = getFrogsWithVitalSigns({

offset: 50,

})

.then((result) => {

console.log(result)

})

.catch((error) => {

console.error(error)

})In the callback code snippet, if we were nested just a few levels deeper, things will start to get ugly and hard to manage.

Problems Occurring From Callback Hell

Just by looking at our previous code snippet representing this "callback hell" we can come up with a list of dangerous issues that were emerging from it that serve as enough evidence to say that promises were a good addition to the language:

- It was getting harder to read

- The code was beginning to move in two directions (top to bottom, then left to right)

- It was getting harder to manage

- It wasn't clear what was happening as the code were being nested deeper

- We would always have to make sure that we didn't accidentally declare variables with the same names that were already declared in the outer scopes (this is called shadowing)

- We had to account for three different errors at three different locations.

- We had to even rename each error to ensure that we don't shadow the error above it. If we ended up doing additional requests in this train of operations, we would have to find additional variables names that don't end up clashing with the errors in the scopes above.

If we look closely at the examples we'll notice that most of these issues were solved by being able to chain promises with .then, which we will talk about next.

Promise Chaining

Promise chaining becomes absolutely useful when we need to execute a chain of asynchronous tasks. Each task that is being chained can only start as soon as the previous task had completed, controlled by .thens of the chain.

Those .then blocks are internally set up so that they allow the callback functions to return a promise, which are then subsequently applied to each .then in the chain.

Anything you return from .then ends up becoming a resolved promise, in addition to a rejected promise coming from .catch blocks.

Here is a short and quick example of that:

const add = (num1, num2) => new Promise((resolve) => resolve(num1 + num2))

add(2, 4)

.then((result) => {

console.log(result) // result: 6

return result + 10

})

.then((result) => {

console.log(result) // result: 16

return result

})

.then((result) => {

console.log(result) // result: 16

})Promise Methods

The Promise constructor in JavaScript defines several static methods that can be used to retrieve one or more results from promises:

Promise.all

When you want to accumulate a batch of asynchronous operations and eventually receive each of their values as an array, one of the promise methods that satisfy this goal is Promise.all.

Promise.all gathers the result of the operations when all operations ended up successful. This is similar to Promise.allSettled, only here the promise rejects with an error if at least one of these operations ends up failing--which eventually ends up in the .catch block of the promise chain.

Promise rejections can occur at any point from the start of its operation to the time that it finishes. If a rejection occurs before all of the results complete then what happens is that those that didn't get to finish will end up aborted and will end up never finishing. In other words, its one of those "all" or nothing deal.

Here is a simple code example where the Promise.all method consumes getFrogs and getLizards which are promises, and retrieves the results as an array inside the .then handler before storing them into the local storage:

const getFrogs = new Promise((resolve) => {

resolve([

{ id: 'mlo29naz', name: 'larry', born: '2016-02-22' },

{ id: 'lp2qmsmw', name: 'sally', born: '2018-09-13' },

])

})

const getLizards = new Promise((resolve) => {

resolve([

{ id: 'aom39d', name: 'john', born: '2017-08-11' },

{ id: '20fja93', name: 'chris', born: '2017-01-30' },

])

})

function addToStorage(item) {

if (item) {

let prevItems = localStorage.getItem('items')

if (typeof prevItems === 'string') {

prevItems = JSON.parse(prevItems)

} else {

prevItems = []

}

const newItems = [...prevItems, item]

localStorage.setItem('items', JSON.stringify(newItems))

}

}

let allItems = []

Promise.all([getFrogs, getLizards])

.then(([frogs, lizards]) => {

localStorage.clear()

frogs.forEach((frog) => {

allItems.push(frog)

})

lizards.forEach((lizard) => {

allItems.push(lizard)

})

allItems.forEach((item) => {

addToStorage(item)

})

})

.catch((error) => {

console.error(error)

})

console.log(localStorage.getItem('items'))

/*

result:

[{"id":"mlo29naz","name":"larry","born":"2016-02-22"},{"id":"lp2qmsmw","name":"sally","born":"2018-09-13"},{"id":"aom39d","name":"john","born":"2017-08-11"},{"id":"20fja93","name":"chris","born":"2017-01-30"}]

*/Promise.race

This method returns a promise that either fulfills or rejects whenever one of the promises in an iterable resolves or rejects, with either the value or the reason from that promise.

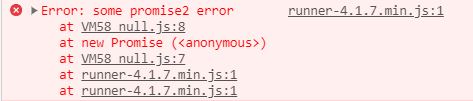

Here is a simple example between promise1 and promise2 and the Promise.race method in effect:

const promise1 = new Promise((resolve) => {

setTimeout(() => {

resolve('some result')

}, 200)

})

const promise2 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

reject(new Error('some promise2 error'))

})

Promise.race([promise1, promise2])

.then((result) => {

console.log(result)

})

.catch((error) => {

console.error(error)

})Which will yield this result:

The returned value ended up being the promise rejection since the other promise was delayed behind by 200 milliseconds.

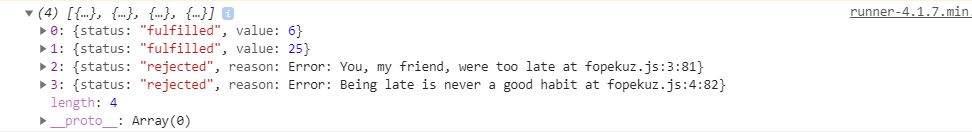

Promise.allSettled

The Promise.allSettled method ultimately somewhat resembles Promise.all in sharing a similar goal except that instead of immediately rejecting into an error when one of the promises fails, Promise.allSettled will return a promise that eventually always resolves after all of the given promises had either resolved or rejected, accumulating the results into an array where each item represents the result of their promise operation. What this means is that you will always end up with an array data type.

Here is an example of this in action:

const add = (num1, num2) => new Promise((resolve) => resolve(num1 + num2))

const multiply = (num1, num2) => new Promise((resolve) => resolve(num1 * num2))

const fail = (num1) =>

new Promise((resolve, reject) =>

setTimeout(() => reject(new Error('You, my friend, were too late')), 200),

)

const fail2 = (num1) =>

new Promise((resolve, reject) =>

setTimeout(

() => reject(new Error('Being late is never a good habit')),

100,

),

)

const promises = [add(2, 4), multiply(5, 5), fail('hi'), fail2('hello')]

Promise.allSettled(promises)

.then((result) => {

console.log(result)

})

.catch((error) => {

console.error(error)

})

Promise.any

Promise.any is a proposal adding onto the Promise constructor which is currently on stage 3 of the TC39 process.

What Promise.any is proposed to do is accept an iterable of promises and attempts to return a promise that is fulfilled from the first given promise that fulfilled, or rejected with an AggregateError holding the rejection reasons if all of the given promises are rejected source.

This means that if there was an operation that consumed 15 promises and 14 of them failed while one resolved, then the result of Promise.any becomes the value of the promise that resolved:

const multiply = (num1, num2) => new Promise((resolve) => resolve(num1 * num2))

const fail = (num1) =>

new Promise((resolve, reject) =>

setTimeout(() => reject(new Error('You, my friend, were too late')), 200),

)

const promises = [

fail(2),

fail(),

fail(),

multiply(2, 2),

fail(2),

fail(2),

fail(2, 2),

fail(29892),

fail(2),

fail(2, 2),

fail('hello'),

fail(2),

fail(2),

fail(1),

fail(),

]

Promise.any(promises)

.then((result) => {

console.log(result) // result: 4

})

.catch((error) => {

console.error(error)

})Read more about it here.

Success/Error Handling Gotcha

It's good to know that handling successful or failed promise operations can be done using these variations:

Variation 1:

add(5, 5).then(

function success(result) {

return result

},

function error(error) {

console.error(error)

},

)Variation 2:

add(5, 5)

.then(function success(result) {

return result

})

.catch(function(error) {

console.error(error)

})However, these two examples aren't exactly the same. In variation 2, if we attempted to throw an error in the resolve handler, then we would be able to retrieve the caught error inside the .catch block:

add(5, 5)

.then(function success(result) {

throw new Error("You aren't getting passed me")

})

.catch(function(error) {

// The error ends up here

})In variation 1 however, if we attempted to throw an error inside the resolve handler, we would not be able to catch the error:

add(5, 5).then(

function success(result) {

throw new Error("You aren't getting passed me")

},

function error(error) {

// Oh no... you mean i'll never receive the error? :(

},

)Conclusion

And that concludes the end of this post! I hope you found this to be valuable and look out for more in the future!